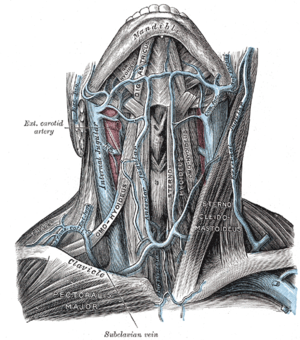

Image via Wikipedia

But first, a little shameless self-promotion: I was recently interviewed for a radio piece on CCSVI that will be airing on National Public Radio this coming Monday, November 1, between 6 AM and 9 AM, during their Morning Edition program (click here to find the NPR station in your area). I have no idea how much of my interview they'll use, and wouldn't at all be surprised if only a few seconds of my voice is heard. Still, it was very flattering to be asked to participate, and it's also very encouraging that NPR is doing a segment on CCSVI, which has been largely ignored by the US media. For everyone who misses the live broadcast, the segment will be archived on the NPR website, and I'll post a link as soon as it's available.

And now, on with the show. I haven't written about CCSVI in quite some time, so the below post is very long, almost twice as long as any other piece I've ever posted. You might want to grab a cup of coffee and a couple of toothpicks to hold your eyelids open before attempting to plow your way through it…

The topic of the vascular theory of MS, which was initially hypothesized by Italian vascular surgeon Dr. Paolo Zamboni, and has come to be called CCSVI (Chronic Cerebrospinal Venous Insufficiency), continues to inflame the MS community among both patients and physicians alike (if you're unfamiliar with CCSVI, please click here). At times the debate over the validity of the CCSVI theory and the efficacy of the procedure used to address it (known as "The Liberation Procedure") has reached the level of hysteria on MS Internet forums, countless CCSVI Facebook sites, and in the print media, with outrageously hyperbolic statements pouring forth from both sides. The most fervent CCSVI advocates claim with absolute certainty that CCSVI is the cause of MS, and that the Liberation Procedure is a cure for the disease, while the theory's staunchest critics label it a hoax, and those physicians practicing the Liberation Procedure con artists selling desperate patients snake oil.

At this stage of the game, when very few scientifically valid trials have been conducted, both extreme viewpoints have absolutely no basis in fact, and these vehement arguments only confuse the issue all the more, creating adversarial tensions precisely when a spirit of open-mindedness and cooperation are desperately needed. Furthermore, these loudly voiced conflicting opinions can only work to the detriment of chronically ill patients vainly searching for answers that simply do not yet exist, adding clutter and confusion to an already complicated issue.

We are in an age of discovery in regards to CCSVI, and over the last several months much has been learned about the condition and the treatment protocols used to address it, though the picture remains far from clear. Many patients, understandably clamoring for easy access to the Liberation Procedure, argue that the procedure is nothing more than angioplasty, which is performed quite commonly on cardiac patients in hospitals around the world, and that they should be given access to the treatment for the simple reason that blocked veins need to be unblocked, regardless of whether or not a patient has MS. Both of these arguments seem quite valid at first glance, but don't really hold up to greater scrutiny.

Angioplasty is indeed a common procedure, and a very safe one at that. The Liberation Procedure, though, is not angioplasty, which is performed on arteries, but venoplasty, performed on veins, a procedure that is done much less commonly. This may seem like a minor discrepancy, but in fact presents some significant challenges to both the doctors performing the procedure and the technologies used during it.

In terms of anatomy, veins and arteries are very different creatures. The major arteries are quite rigid, designed to withstand the intense pressure of blood being pumped through them by the beating heart. Thus, when they are ballooned or stented open during angioplasty, they tend to stay open, given their natural rigidity. Veins, on the other hand, are thin-walled and flexible (just play with the ones on the back of your hand to see what I mean), presenting a very different target for the balloons or stents used during the Liberation Procedure. Virtually all of the equipment used during the Liberation Procedure was originally designed for utilization in arteries, and this has led to less than ideal efficacy when used in veins, as I will discuss in more detail a bit later. From a safety standpoint, as long as the procedure is confined to the use of balloons to open narrowed or blocked veins, the Liberation Procedure is quite safe.

As for the assertion that blocked veins need to be unblocked regardless of the overall health of the patient, this too is not as clear-cut as it first may seem. Since arteries are the primary culprits in cardiac disease and strokes, human venous anatomy has been very little studied by modern medicine. Incredible, but true. I've been told by several radiologists and vascular specialists (including those at the National Institutes of Health) that there truly is no definition of "normal" that can be used as a benchmark when assessing an individual patient’s venous system.

Indeed, initial studies have shown that up to 25% of healthy people appear to have the vascular blockages known as CCSVI, to no apparent ill effect (click here for info). Venous anatomy is redundant and adaptable, and it had been thought that blockages in veins are largely compensated for by this adaptability. Blood flow blocked in one vessel was assumed to be simply routed through another, or through new vessels grown by the body to make up for the blockage, called collaterals. Perhaps one fringe benefit of the investigation into CCSVI will be closer attention paid to venous anatomy on the whole.

It's important to keep in mind that Dr. Zamboni's theory involves not only blockages in veins, but more precisely, the reflux of deoxygenated blood back into the central nervous system caused by those blockages. Therefore, not all venous blockages meet the requirements of CCSVI.

My own case is a perfect example. A catheter venogram revealed that I have a significant blockage in my right internal jugular vein. Further testing indicated that this blockage is quite unusual, as it is not caused by an abnormality internal in the vein, as is the usual case, but rather by an external muscle pinching the vein significantly closed. The Interventional Radiologist who did my procedure reviewed my case with Dr. Zamboni, who is of the opinion that although my vein is clearly blocked, this blockage has not resulted in a turbulent backflow of blood, and therefore should not be treated. Not really what I wanted to hear, but facts is facts. I do plan on getting further testing to confirm Dr. Zamboni's opinion.

Earlier this month, one of the major international MS conferences took place in Sweden. Known as ECTRIMS (European Committee on Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis), this year's conference featured many presentations on CCSVI, which in itself is something of a victory. During last year's conference nary a word about CCSVI was mentioned.

Much of the evidence presented at ECTRIMS was mixed, on the whole seemingly confirming a correlation between Multiple Sclerosis and the vascular abnormalities known as CCSVI, but also casting some doubt as to whether or not CCSVI is a cause, rather than an effect, of Multiple Sclerosis. Dr. Robert Zivadinov, who leads the team of researchers vigorously investigating CCSVI at the University of Buffalo, presented several very interesting papers. One paper demonstrated that the severity of CCSVI increases with the severity of Multiple Sclerosis symptoms experienced by patients, and with a more advanced disease course (click here for abstract). These findings were backed up by papers presented by researchers from Beirut (click here for abstract) and Italy (click here for abstract). If CCSVI were the cause of MS, the researchers would expect that a constant level of vascular abnormalities would be seen across the entire spectrum of disability levels and duration of disease among patients studied, which is not what their studies demonstrated. Other research presented at the conference contradicted these findings, such as a paper presented by Dr. Marian Simka, an Interventional Radiologist in Poland who has done hundreds of Liberation Procedures, which found that CCSVI plays a role in the cause and progression of MS, and that the vascular abnormalities were most likely congenital (click here for abstract).

Another study presented by Dr. Zivadinov found that subjects who presented with CCSVI had significantly more lesions and brain atrophy as measured by MRI than those MS patients without vascular abnormalities (click here for abstract). Yet another investigation presented by Dr. Zivadinov looked at the correlation between a gene implicated with MS, and CCSVI, and found that the data supported an association between MS disease progression and CCSVI separate from the suspect gene. The implications of these findings are that CCSVI could be a risk factor in developing the disease, or a result of the progression of MS (click here for abstract).

Clearly, the data presented at ECTRIMS was a mixed bag, which some CCSVI advocates found disappointing in that much of the evidence offered did not point to CCSVI being a direct cause of MS. Still, the studies did reveal a very strong correlation between vascular abnormalities and Multiple Sclerosis, which in itself is a giant step forward in convincing a dubious scientific community that these abnormalities do play a significant role in the puzzle that is MS. Much more research is needed to resolve the challenging questions posed by CCSVI, and such research is ongoing at the present time in multiple locations worldwide.

Some staunch CCSVI advocates have tried to dismiss research with findings not to their liking by claiming that the methodology used was faulty, or that the researchers themselves were tainted by their associations with pharmaceutical companies. As for the methodology used, it may be different than that originally used by Dr. Zamboni, and thus might in fact be invalid, but it does occur to me that the physical abnormalities found in CCSVI are not subtle in nature. We are talking about rather severe blockages in blood vessels, significant enough to cause blood to actually flow backwards through those vessels. It would seem that abnormalities of this magnitude should be detectable by more than one set of extremely specific methods of measurement. But, as I stated previously, venous anatomy has been little studied in the past, so perhaps the technological choices are indeed limited.

As for researchers whose integrity has been compromised by their ties to pharmaceutical companies, if all such physicians were prohibited from taking part in research studies, there would be practically no medical research conducted at all. A tragic truth about our current medical system is that almost every physician practicing in the United States has some affiliation with a pharmaceutical or medical device company. This phenomenon is not limited to neurologists, as some would make it seem, but is epidemic throughout the medical community. A wide range of doctors have affiliations with drug companies; orthopedic surgeons have relationships with the makers of artificial joints (click here for a fascinating New York Times article on this), cardiac surgeons are courted by the makers of replacement heart valves, and Interventional Radiologists have associations with the makers of the stents, catheters, and balloons with which they ply their trade. I've said it before, and I'll say it again, capitalism is a wonderful engine for driving an economy, but is absolutely corrosive when applied to the practice of medicine. When patients are viewed first as consumers of medical products and services, something is seriously wrong. I previously expounded on this disturbing topic in a previous post, "The Medical Industrial Complex: Sick People Required", which you can access by clicking here.

One of the big problems involved in the study of CCSVI in that none of the noninvasive imaging techniques used to try to detect venous abnormalities in patients before having them undergo an invasive catheter venogram are all that reliable. MRV imaging in particular has proven to be almost worthless, as yet another study conducted by Dr. Zivadinov and presented at ECTRIMS demonstrated (click here for abstract). Doppler Sonography, while more accurate, is only useful in detecting CCSVI when used according to very specific protocols, and conducted by a highly skilled operator. Even when such conditions are met, Sonography is somewhat subjective, as the Zamboni trained sonographer who did my Doppler scan has said. Sonograms can be interpreted differently by different physicians, and time after time both MRV and sonogram imaging done on patients have proven to be unreliable once a catheter venogram is performed. The blockages suggested by the noninvasive techniques simply don't correspond to what is actually found in patients when the catheter is inserted into their veins.

While the academic questions regarding CCSVI are all very interesting and fodder for great controversy, the biggest question for those of us suffering from Multiple Sclerosis is whether or not the Liberation Procedure can relieve our symptoms. If it turns out that the procedure is a cure, well, then MSers have hit the jackpot. If liberation "only" results in a dramatic drop-off in the misery caused by the disease, it's still a huge win, and will forever change the way MS is researched and treated. More importantly, hundreds of thousands of MS patients around the world will have a new and relatively straightforward conduit to relief.

Since no formal treatment studies have been conducted thus far (several are currently underway), we can only rely on the anecdotal accounts of patients who have undergone the Liberation Procedure when assessing its effectiveness. It's been estimated that over 2000 procedures have been performed in various locations around the world, but we've only heard from, at most, perhaps 100-150 of these patients. When assessing these accounts, which are usually quite encouraging, it's important to keep in mind that the preponderance of mostly positive reports related on Internet forums and YouTube videos are a product of the natural phenomenon of people who have positive outcomes to be much more inclined to make their results public than those with negative experiences. This isn't an attempt at subterfuge on anybody's part, but merely human nature. Reports from several clinicians doing the Liberation Procedure indicate that the success rate is less robust than might be inferred from Internet accounts. Still, some important trends can be identified in the anecdotal reports available.

It does appear that the Liberation Procedure does positively impact MS symptoms for a significant portion of the patients on whom it is performed. These positive results range from dramatic to slight, but another significant portion of patients, albeit a minority, report receiving no benefit from the procedure at all, some even telling of a worsening of their condition post procedure. We are also seeing the very troubling trend of restenosis (veins closing back up) several weeks or months after balloon venoplasty, and also an increasing amount of accounts of problems with stents implanted in patients' jugular veins, primarily in the form of stent thrombosis (clotting), and stented veins stenosing in areas above or below the location of stent implantation.

Although the accounts of restenosis are discouraging for the patients who experience it, their stories speak loudly to the validity of the CCSVI hypothesis and the effectiveness of the Liberation Procedure. Patients tell of experiencing marked improvements after having had the procedure, but then a dramatic worsening when their veins once again collapse. Upon a second attempt at liberation, most of these patients once again experience benefit. Unfortunately, many of these patients restenose yet again, accompanied by the return of their MS symptoms. This is a strong indication that resolving vascular blockages at the very least results in symptom improvement for a significant number of MS patients. However, with the incidence of restenosis far too common, strategies must be developed to address this vexing problem. Obviously, patients can't be expected to undergo repeated invasive procedures (which include a not insignificant dose of radiation) to address a continuing pattern of restenosis.

Stents have been used to treat veins that were resistant to ballooning or were otherwise problematic. The use of stents in the jugular veins has been somewhat controversial from the outset, as all of the available stents were designed for use in arteries, which generally carry a much more robust blood flow than veins, and which narrow in the direction of blood flow. This means that the risk of clotting in arterial stents is much less than in veins, and that any stent getting loose in an artery would only get pushed further into that artery, rather than have a clear path to the heart, which is the case for stents implanted in the jugulars.

As accounts of problems with stents increase, several doctors and clinics that perform the Liberation Procedure have shied away from using them. Since, once implanted, stents generally cannot be removed, the long-term failure rates of stents are also of considerable concern. The only other patient population that regularly receives venous stents are late stage renal patients, whose veins collapse as a result of kidney dialysis. Studies of the patency rates of stents placed in these patients are less than encouraging, finding failure rates as high as 50% after one year (click here for info). While the two patient populations in question are extremely different, the risk of stent failure in the long term is a legitimate concern, especially since the currently available stents were designed for use primarily in thoracic arteries, where they're not subject to the constant bending, twisting, and torque they experienced when placed in the very flexible human neck. Whether or not to allow the use of stents is among the many very difficult decisions patients considering liberation must make. I personally decided that I would not allow their use.

Obviously, large-scale treatment studies are desperately needed to determine not only the efficacy of the Liberation Procedure, but also the best methods and practices for performing it. Currently, the techniques used vary widely from doctor to doctor, with no real consensus among the treating physicians regarding the size of balloons to use during venoplasty, the use and placement of stents, or even what constitutes a treatable stenosis. Furthermore, many of the Interventional Radiologists performing the procedure have commented on the rather steep learning curve involved in getting it right.

Increasingly, it appears that the CCSVI picture is more complicated than originally thought, with more blood vessels (including the lumbar, iliac, and vertebral veins) likely involved. The Liberation Procedure is a work in progress, and procedures done a year from now will probably differ significantly from those done today. Physicians are still in the early learning stages in regards to the treatment of CCSVI, and patients should be wary of being a part of anybody's learning curve. The success rate of Interventional Radiologists who have done numerous procedures appears to be much greater than those with less experience. Again, the decision of what physician to choose needs to be given very careful consideration by patients considering liberation; not just any doctor offering the procedure will be adept in its performance. There is increasingly a "Wild West" environment developing out there, as the prospect of huge financial gains made by offering the Liberation Procedure becomes apparent to physicians worldwide, who might undertake the procedure without the proper training and requisite experience. This is a pitfall that patients need to be very aware of, and must be very careful to guard against. Ask any potential treating physician serious questions, request patient references, and do as much research as possible. Until the myriad questions regarding CCSVI and its treatment are fully resolved, there will be plenty of opportunities for hucksters to take advantage of desperate patients.

A burgeoning medical tourism industry has sprung up around CCSVI, with clinics offering the Liberation Procedure in such diverse locations as Poland, Bulgaria, India, and Costa Rica, for prices generally ranging from $10,000-$20,000. Because of the persistent problems with restenosis, stent thrombosis, physician competency, the necessity for post procedure medical care, and the constantly evolving knowledge base regarding the best standards and practices of the Liberation Procedure, I strongly urge patients to forgo traveling long distances for treatment.

In a best case scenario, in which a patient travels thousands of miles and spends heaps of money to be treated with balloon venoplasty, and finds themselves to be amongst those lucky enough to see significant benefit from the procedure, there is still the large risk (some place it at 50%) of restenosis some weeks or months post procedure. In such a case, the patient would be back to square one, less the large amounts of money they spent on travel and the procedure itself.

Furthermore, aftercare is very important, as patients are commonly placed on blood thinning drugs post procedure. These drugs need to be carefully monitored for months after treatment. If a stent is implanted, it may be quite difficult for patients experiencing complications to find appropriate treatment locally, with the possibility of dire consequences. Keep in mind, too, that there is no guarantee that any given patient will be among those who experience dramatic improvement. One prominent Interventional Radiologist that has performed well over 100 Liberation Procedures estimates that one third of his patients see no benefit from the procedure. Given those odds, combined with the high risk of restenosis and the very small but real chance of medical complications that might arise after liberation, traveling long distances and spending tens of thousands of dollars to pursue treatment cannot be recommended.

Of course, every patient must make decisions regarding CCSVI and the Liberation Procedure based on their own unique circumstances. For the majority of patients, I would strongly advise waiting 6 to 12 months before seeking liberation, as much more information from both academic and treatment research studies will be available, and some standardization and identification of best practices will be achieved in the coming months by the Interventional Radiologists performing the procedure.

It's very important, and very difficult, to make an unemotional and accurate assessment of your own condition and rate of progression. Karen likes to chide me about the fact that I've been saying that I'm six months away from being bedridden for the last three years. Presently, my right side is almost completely paralyzed, and my left side is weakening considerably. Not a good combination. I understand the desperation that all MS patients feel, regardless of the particulars of their state of disability. We all want to just be rid of this disease. But unless your situation is genuinely dire, it will absolutely be in your best interest to allow the science of CCSVI and the techniques that go into the Liberation Procedure to mature, as doctors gain experience and more hard facts about the condition become available. Most MS patients experience a relatively slow progression of disability. Waiting, especially in the face of the hype surrounding CCSVI, is extremely difficult, but in this case might save you considerable bodily wear and tear, significant sums of money, and much heartache. If your situation is genuinely dire, and your condition is rapidly declining to the point that your quality of life soon will be nonexistent, then all bets are off. Do what you feel needs to be done.

I firmly believe that CCSVI will prove to play a major part in the MS puzzle. Like all things related to MS, its impact will vary from patient to patient. For some patients, it may very well be THE answer to their problems, for others only a partial solution, and for others still it may play no role at all. MS is a very complex and frustrating disease, truly a scourge to those who suffer from it. CCSVI offers a light at the end of the tunnel, but there is still much work that needs to be done. Thankfully, dedicated researchers and physicians are actively looking for answers, even in the face of sometimes withering criticism, and their findings may very well result in paradigm shattering changes that rock the world of MS. But it is still very early in the game, and it's important to remember that discretion is often the better part of valor, and that the race does not always go to the swift.

![Room[1] Room[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhCxNYFifBguH3_7DLwep_YwoyWOSWlOFwdlLjB-8r0sE1KMy8bU9ynerTrjvYpFOe7pUfdG37nkEdr5WP489pHcwY4GecabMBR2x1dFUyTVhqt2KGwUUl0wd5qn4PqC8gLeRAVFMGi3hs/?imgmax=800)