Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

A few months ago, I published a post about a radical new theory regarding Multiple Sclerosis, called the "Cerebrospinal Venous Insufficiency" theory, or CCSVI for short. I thought that now might be a good time to provide an update.

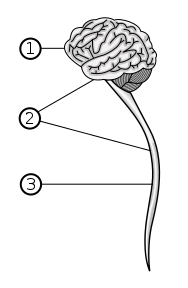

Just to review, several years ago researchers in Italy started looking at the vascular systems of MS patients, specifically by imaging the veins that are directly related to the central nervous system (the jugular and azygous veins). Incredibly, they found that in nearly all of the patients they studied there were blockages or abnormal narrowing of these very important vascular pathways. The researchers theorized that the vascular blockages they were finding could cause a reflux of blood back into the central nervous system, which in turn could lead to inflammation and edema, and eventually to a breakdown in the blood brain barrier, and thus be responsible for the damage seen in Multiple Sclerosis. About two years ago, the doctor leading this research, Dr. Paolo Zamboni, started performing modified balloon angioplasties on these areas of abnormality.

An interventional radiologist at Stanford University, Dr. Michael Dake, became interested in this research after it was brought to his attention by the activist wife of an MS patient. Dr. Dake traveled to Europe to meet Dr. Zamboni, and upon his return started doing some investigations of his own. He too found serious vascular abnormalities in nearly all of the MS patients he imaged. Based on these imaging studies, approximately 4 months ago Dr. Dake started performing endovascular surgery on these patients, placing stents in blocked veins to open up the areas of abnormality that he found.

To date, Dr. Dake has performed surgery on about 35 patients, most of whom have reported positive results as a result of the surgery. Although most of the patients who have undergone the procedure were not severely disabled due to MS, they all suffered from the usual array of MS symptoms, including cognitive dysfunction, heat intolerance, and severe fatigue. Many also suffered from varying degrees of motor and sensory dysfunction. Almost all have reported marked improvements in these areas.

Tragically, one of the patients who underwent the procedure died of a massive cerebral hemorrhage soon after, but the consensus is that the patient’s stroke was not directly related to the endovascular surgery that was performed. The blood thinning medication that was given postsurgery did contribute to the severity of this terrible event, but was not deemed to be a causative factor.

Dr. Zamboni recently published a summary outlining the results he's seen on the patients who were treated with his endovascular procedure, which he calls the "Liberation Procedure". In the 51 RRMS patients treated with the procedure, Dr. Zamboni claims a fourfold decrease in relapses. Furthermore, Dr. Zamboni performed the procedure on 18 patients who were suffering from acute relapses, and after surgery these patients recovered from their relapses in time periods ranging from four hours to four days. Dr. Zamboni cites this as "the best evidence that venous obstructions play a causative role in the complex pathogenesis of Multiple Sclerosis".

Dr. Zamboni and his team have organized a conference on "Venous Function and Multiple Sclerosis", to be held in Bologna, Italy on September 8 of this year. Several prominent US neurologists specializing in MS are expected to participate.

It's important to note that Dr. Zamboni's surgical results have been self-reported, and not subject to peer review. Additionally, no MRI imaging studies were done on his patients after they underwent the "Liberation Procedure", which would have been very valuable in assessing the impact the procedure had on the central nervous system lesions of those who underwent it.

Dr. Dake is planning on starting his own clinical study in September, 2009, which is expected to be limited to RRMS patients.

All of this information is extremely fascinating, and may offer a brand-new approach to understanding and treating Multiple Sclerosis. It's very important to keep in mind, though, that nothing has yet been proven, and that all of the results so far reported, as positive as they've been, have only come from two sources (Dr. Zamboni, and Dr. Marian Simka, who has done research on CCSVI in Poland). Scientific discipline requires that these results be replicated by independent researchers before anything definitive can be stated about this theory, and I expect that several groups will be attempting to do just that in the near future.

I personally find this research to be quite exciting, although I am maintaining a healthy skepticism regarding it. In my 6+ years as an MS patient, I've seen many such "theories du jour" generate tremendous enthusiasm, only to be disproven by the greater scientific community. In this case, though, my gut tells me that there might be something to this. I'm quite sure that this theory can't explain all cases of MS, but it does seem compelling enough to suggest that, at the very least, there is a subset of patients for whom the root cause of MS may not be neurologic or autoimmune, but vascular.

Research into the causes and treatments of Multiple Sclerosis has fallen almost exclusively into the realm of the neurology and neuroimmunology communities for the last 30 or so years. Though some impressive advances have been made, the disease has proven to be quite confounding when looked at from these perspectives. CCSVI offers a fresh approach at understanding the disease, and furthermore, offers the hope of some straightforward methods of treating it.

This research may turn out to be nothing but a flash in the pan, but there is the chance that it could revolutionize our understanding of Multiple Sclerosis. For this reason, I recommend that all MS patients pay close attention as the CCSVI story unfolds...

Update 11/21/09: Canadian television has done in a news report on CCSVI. Click here for the link.

Update 11/30/09: CCSVI: Separating Fact from Fiction. Click here.

Receiving a diagnosis of MS, or any serious illness, is a reality shattering event. Despite the initial wave of fear, confusion, and consternation, there is one thing the receiver of such news knows innately; life as they know it will very likely never again be the same. Whether the disease eventually takes a mild course, leaving a person relatively intact for an extended length of time, or a more aggressive path, as in my case, landing its victim in a wheelchair within five years, life's future trajectory has been fundamentally altered. If not by the ravages of the disease itself, a patient's reality will be warped by the sudden realization of their absolute vulnerability.

Receiving a diagnosis of MS, or any serious illness, is a reality shattering event. Despite the initial wave of fear, confusion, and consternation, there is one thing the receiver of such news knows innately; life as they know it will very likely never again be the same. Whether the disease eventually takes a mild course, leaving a person relatively intact for an extended length of time, or a more aggressive path, as in my case, landing its victim in a wheelchair within five years, life's future trajectory has been fundamentally altered. If not by the ravages of the disease itself, a patient's reality will be warped by the sudden realization of their absolute vulnerability.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=61d4a5d0-0691-4391-9a84-0fb43c632b03)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=2d499db4-5425-49b1-acc8-7af19973638a)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=aa3e6576-316c-4dfe-b006-4e954d80377e)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=1fd6b9b5-77bc-45fb-8b24-0070d8bfe423)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=88b343c7-ad0f-48bc-ad05-794a8e511e24)