| Image via Wikipedia |

It seems almost incredible, but it's been nearly 3 years since I wrote my first Wheelchair Kamikaze post on CCSVI (click here). At the time of that first post, CCSVI had hardly been heard of outside of some researchers in Italy and a few dozen patients debating the merits of the hypothesis on an Internet forum. Today, CCSVI has become a patient driven social media medical phenomenon. An estimated 25,000-30,000 patients have already undergone CCSVI treatment, researchers from around the world are investigating the hypothesis, and the surgical treatment of CCSVI has become a thriving industry. CCSVI has certainly come a long way, but in many ways we've only taken the first steps on what could be an epic journey.

Last week, the International Society for Neurovascular Disease (ISNVD) held its second annual scientific meeting, which lasted five full days, in Orlando, Florida. A tremendous amount of information about the nature and treatment of CCSVI was exchanged by researchers and physicians, a compendium of which can be found in a 106 page online PDF publication put out by the Society (click here).

Of most interest to patients are undoubtedly the treatment outcomes reported by several CCSVI treatment practitioners (which can be found on pages 62, 79, 83, 84, 86, and 87 of the PDF), which displayed a wide variety of treatment outcomes, but do seem to suggest several identifiable trends. It appears that quality of life issues (fatigue, cognitive issues, heat sensitivity) saw more benefit post treatment than mobility related issues, and that RRMS patients fared better than patients suffering from SPMS or PPMS. None of these studies was double blinded, all being observational and most relying on self-reported information, which can lead to inaccuracies. Still, the findings generally fall in line with some of the few double blinded studies that have been done, such as a recently completed study done in Italy (click here). CORRECTION:an anonymous reader points out that this Italian study was in fact not double blinded, and just used an independent physician to evaluate EDSS scores. Thanks for the heads up.

The meeting did bring into focus the fact that the CCSVI treatment protocol is far from standardized, with physicians varying in opinion on issues ranging from which veins to treat, whether treatment should concentrate on valves rather than the veins themselves, the use of intravascular ultrasound, and other important issues, a list of which can be found on pages 104-106 of the PDF document linked to above. There were quite a few presentations on the use of noninvasive imaging techniques (Doppler Ultrasound and MRV technology) to diagnose CCSVI, with the consensus appearing to be that neither method was especially accurate, except for extremely specialized MRV protocols that are practiced at only a few facilities. One leading CCSVI practitioner went so far as to state that he no longer requires his patients to undergo Doppler Ultrasound investigations before venoplasty, since the ultrasound results were found to be so prone to error (page 63 of the PDF).

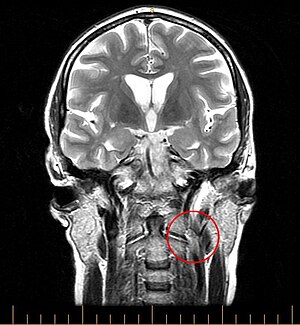

In addition to presentations involving CCSVI treatment techniques, some important observations about the nature of the condition were also presented. The effects of reduced blood flow through the brain were discussed, as was the possible connection between bloodflow disruptions and a breakdown of the blood brain barrier, and the role of iron deposition in the MS disease process. In all, my impression (keeping in mind that I did not attend the meeting) is that the findings presented at this year's ISNVD scientific meeting were more evolutionary than revolutionary, which I suppose is something to be expected. The explosion of interest in CCSVI amongst interventional radiologists and research physicians must logically lead to attempts to fill in the many gaps of knowledge that remain in regards to CCSVI, before more dramatic leaps in understanding can be accomplished.

This eruption of interest in CCSVI within the interventional radiology community is in some ways a double-sided sword. On the plus side, it has given patients access to treatment, which in the early days was extremely hard to come by. Today, patients have their choice of treating physicians, and must do their due diligence when choosing which physician in whose hands to place themselves. As noted above, treatment techniques and philosophies vary widely from physician to physician, and patients exploring the possibility of CCSVI treatment should not be shy about asking questions in an effort to find a doctor whose treatment modality best fits their comfort level.

On the potentially negative side, CCSVI has become big business. With CCSVI treatment procedures costing about $10,000, and somewhere between 25,000-30,000 patients already treated, a little math reveals that treating CCSVI has already generated hundreds of millions of dollars in gross revenue for treating physicians. Yes, those procedures covered by medical insurance probably don't get reimbursed at the full rate charged, but this is likely made up for by patients who have undergone multiple procedures because of CCSVI's ongoing problems with restenosis. Given the fact that the number of treated patients represents only a tiny percentage of the worldwide MS population, it's easy to see that CCSVI treatment could quickly develop into a multibillion-dollar a year enterprise.

The David vs. Goliath narrative that has driven the CCSVI story thus far may soon become obsolete. To be sure, the neurology community still remains incomprehensibly steadfast in its negativity regarding CCSVI, but this is becoming counterbalanced by the enthusiasm of the interventional radiology community, and, I suspect, by the interests of the medical device manufacturers, who also stand to profit greatly should CCSVI become an accepted treatment option for MS patients. Despite the fact that very legitimate issues remain regarding the efficacy of CCSVI treatment and the lack of a consensus as to optimal interventional techniques, CCSVI treatment is being aggressively marketed by several US and international treatment facilities, which should raise some ethical questions.

Until issues with effectiveness and technique are satisfactorily answered, the CCSVI treatment procedure must be considered an experimental one, a fact that should not be lost on patients who are understandably desperate to address their illness but are faced with a dizzying array of statistics, patient testimonials, and marketing efforts by for-profit ventures. In a very real way patients who choose to undergo CCSVI treatment at the current time are guinea pigs, a fact that I understood explicitly when I underwent my venoplasty back in the dark ages of CCSVI, almost two years ago. Although we've come a long way since then, in some ways the procedure remains as experimental as ever, as physicians treat a much wider array of veins much more aggressively than they did back when I underwent the procedure. Though the treatment is a minimally invasive one, it is not without risks, as is evidenced by the contingent of patients who have experienced clotting issues and vein thrombosis in the aftermath of their procedures. Indeed, one of the presentations at ISNVD highlighted a patient whose condition worsened after treatment (page 89 of the PDF), a rare occurrence to be sure, but a possibility that must factor into the decision-making process of patients considering venoplasty.

One of the most volatile controversies raging on CCSVI forums and social media sites is whether or not the condition is a cause or effect of multiple sclerosis, with those arguing for CCSVI as cause often citing the fact that the venous abnormalities being found appear to be congenital (developed in the womb) in nature. I am unsure as to the question of cause vs. effect, although I do believe that if CCSVI is a cause of MS, it is only one of many factors involved in the initiation of the disease. Even if the vascular defects being found in the veins of MS patients are congenital, this does not necessarily mean they are a cause of multiple sclerosis. There are many congenital defects that cause no adverse effect whatsoever, and I'd venture to say that many of us have some physical trait somewhere in our bodies that is outside of normal variance.

We've all heard stories of world-class athletes suddenly collapsing during or directly after extreme physical exertion. Quite often, the follow-up story is that the unfortunate athlete was a victim of a congenital heart defect, which would never have been noticed had that person not pushed his body to physical extremes. Had they not been athletes, they very well could have lived a normal life span. Likewise, a person born with congenitally abnormal ligaments in their knees might never know of their condition unless they encounter an environmental element (such as a hit to their knees) that brings their abnormality to the fore, in the form of a knee injury more severe than that which might have been suffered by a person with "normal" ligaments. Given the varied elements that have been linked to MS (infectious agents, exposure to toxins, vitamin deficiencies, genetic markers, etc.), a likely scenario is that vascular abnormalities play a part in predisposing an individual to developing MS when exposed to an unfortunate storm of other factors.

To my mind, it is becoming increasingly clear that, despite our greatest hopes, CCSVI is only a part of a much bigger and more complex MS picture. Precisely how big a part it plays is still open to question. Although CCSVI treatment does appear to benefit many patients, it has also been shown to be of little or no value to many others. CCSVI does not explain some of the factors that have previously been established about MS, such as the geographic distribution of the disease (click here), the male-female ratio that is well known to exist in MS (click here), the existence of "multiple sclerosis clusters" (which would seem to point to an infectious cause-click here), or the unmistakable link between MS and Epstein-Barr virus (click here). Nevertheless, CCSVI offers the promise of opening up whole new areas of research into the causes of, and treatments for, multiple sclerosis. Certainly, interested MS patients should investigate the possibility of CCSVI treatment, and make a sober assessment as to whether now is the proper time for them to jump in.

There are several ongoing research projects that should further illuminate the CCSVI picture scheduled to publish results later this year, but further robust and expeditious research is desperately needed. It is essential that we ascertain just how prevalent CCSVI is in the healthy population, gain a better understanding of the role, if any, of vascular abnormalities in the MS disease process, determine which MS patients respond best to CCSVI venoplasty, refine the techniques used to treat CCSVI, reduce the number of patients who experience restenosis, and see the development of surgical implements specifically designed to treat venous abnormalities. Neurologists need to get on board to provide interdisciplinary expertise to CCSVI studies. After all, whatever the results of the research, positive or negative, answering these questions can only be in the best interest of their patients.

CCSVI has come a long way, but there is still a long way to go. Thankfully, the pace of CCSVI research is gaining momentum, and hopefully we will see answers to many of our questions sooner rather than later. In the meantime, my best advice is to educate yourself to the best of your ability, be your own most powerful advocate, and make treatment decisions based more on reason than emotion.