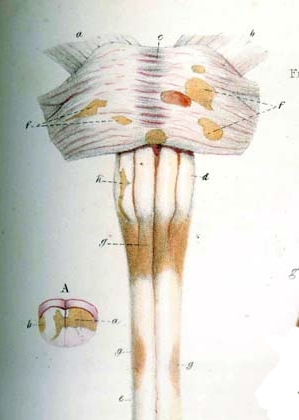

Image via Wikipedia

As most patients know, diagnosing Multiple Sclerosis is no easy matter. Despite sophisticated diagnostic tools and techniques, such as MRI imaging, spinal fluid analysis, and visual and sensory evoked potentials, the diagnosis of MS remains one of exclusion, meaning that other likely diseases must be eliminated before a conclusive diagnosis of MS can be made. There is no test or tests that can definitively determine whether or not a patient is suffering from MS. There are indicators that are strongly suggestive of MS, such as brain and/or spinal cord lesions seen on MRIs, and oligoclonal bands (O-bands) in the Cerebrospinal Fluid, but even the presence of these does not guarantee that a diagnosis of MS is correct.

Although MRIs can detect lesions in the CNS, they can't determine specifically what those lesions are, as a tumor and an area of demyelination can often look much the same on an MRI image. Therefore, a subjective determination of the nature of any lesions found must be made by a radiologist or neurologist. O-bands in the CSF indicate immune activity in the CNS, but they are not specific to MS, as other conditions can also create them. A relapsing remitting course of disability onset is highly suggestive of Multiple Sclerosis, but this too does not rule out other disease possibilities, and some MS patients present with a progressive course of the disease. In the book " Multiple Sclerosis: Diagnosis, Medical Management, and Rehabilitation", neurologist P. K. Coyle writes:

"… early accurate diagnosis is critical. It guides optimal therapy, removes uncertainty, allows informed planning, and improves the patient's sense of well-being by providing an explanation for their problems. Unfortunately, the misdiagnosis rate for MS approximates 5% to 10%, even by experienced healthcare providers"

In an effort to cut down on the number of misdiagnoses, in 2001 a set of diagnostic guidelines was developed, called The McDonald Criteria (click here), that attempts to quantify the test results and clinical presentations necessary for a definitive diagnosis of each of the various forms of MS. In 2009, however, I took part in a study at the National Institutes of Health (the United States government's medical research facility) that was designed specifically to look for patients with Clinically Definite Multiple Sclerosis (more on my experience in the study later). The NIH undertook this study because they had found that the rate of misdiagnosed patients recruited for their MS research studies was at least 10%, and the data from these patients was polluting their research results. The doctors at the NIH were attempting to identify a pool of patients that they were confident actually have Multiple Sclerosis for use in future studies.

There are many diseases and conditions that can be mistaken for MS, including Lyme Disease, Hughes Syndrome, Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Neuromyelitis Optica, Vitamin B12 Deficiency, and Lupus, to name a few. The paper "The Differential Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis" (click here) gives a comprehensive overview of the many red flags that doctors must look for when diagnosing MS, and includes a list of 100 diseases that can be misdiagnosed as MS. Another valuable paper on the topic, "Differential Diagnosis of Suspected Multiple Sclerosis: a Consensus Approach" (click here) provides a list of symptoms that should lead a physician to question a diagnosis of MS, and discusses four of the diseases most likely to be misidentified as MS.

If you have reason to question your diagnosis, the above materials can be invaluable. However, be careful not to drive yourself crazy with the information they contain, as they provide so much data that it's very easy to convince yourself that you've been wrongly diagnosed. Even with a misdiagnosis rate of 10%, the vast majority of patients have in fact been given the correct diagnosis.

My own case illustrates the difficulties involved with reaaching a conclusive diagnosis of MS, to the extreme. I had doubts about my diagnosis almost from the day I received it. Although my initial presenting symptom (a slight limp) was very typical for someone with PPMS, the more I read up on the disease, and interacted with other patients who had it (mostly online), the less convinced I became that the diagnosis was correct. I'd been having strange symptoms for years (antibody-based thyroid disease, possible discoid lupus, a variety of endocrine problems ) and my MRIs showed only two lesions, a tiny one in my brain, and a larger, much more invasive lesion at the base of my brainstem. In addition, my spinal fluid results were always normal, showing no O-bands.

As time went on, my disease continued to behave strangely, initially attacking only my right side. Despite the relentless progression of my disability, my MRI images never changed, and haven't to this day. They still show only those same two non-enhancing lesions, which haven't changed in size or shape since they were first seen over eight years ago. My MRI images from 2003 look exactly like the ones I had taken last month, but compared to 2003, I'm now a physical wreck. I switched neurologists one year after my diagnosis, and my new neuro also initially suspected that I might not have MS. I underwent a comprehensive series of tests and scans trying to uncover an alternate culprit, all to no avail. Everything came back negative, and, since MS is a diagnosis by exclusion, the only candidate left standing was Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. So, I was left with the label "atypical PPMS".

Never one to settle for something I wasn't sure of, especially something as important as the diagnosis of a progressively crippling disease, I set about on a quest for second and third (and fourth) opinions. I visited infectious disease doctors who specialized in Lyme Disease, but very specialized blood tests came back negative. I scheduled an appointment at the Johns Hopkins MS center, in Baltimore, and was examined by Dr. Peter Calabresi, one of the biggest names in MS research. He too found my disease presentation strange, and ordered an extensive series of tests, which included the taking of over 30 vials of blood (yikes!), but these too all came back negative. So, Johns Hopkins also concluded that I have "atypical PPMS". "How atypical does a disease have to be before it's not that disease?", I asked to all who would listen, but never really got a good answer.

My primary neuro, Dr. Saud Sadiq, who is himself a highly regarded physician, occasionally sent me for various tests and poking and prodding, just to check that we hadn't missed something. Always, the results came back negative. I kept in touch with Dr. Calabresi from Johns Hopkins, and two years after he first examined me, I sent him some of my latest MRI images, which looked exactly like my old MRI images, and told him that my disease had progressed significantly. As this seemed extremely strange, he asked that I come down for another examination. After another neurologic workup, Dr. Calabresi concluded that he had strong doubts that I had MS, but couldn't figure out what it was I did have. He suggested I might have a mitochondrial disorder, or Sjogren's disease. Off I went to see one of the most noted mitochondrial disease specialists in the states, who quickly determined that my mitochondria were fine. I had a lip biopsy done looking for Sjogren's disease, but, of course, it came back negative…

It was then that I learned of the study being done at the NIH, which cast a wide net looking for MS patients to examine, trying to find a sizable pool of candidates that the NIH researchers could be confident had Clinically Definite Multiple Sclerosis for use in future studies. At first they were reticent to accept me into the study, as they generally weren't taking patients more than a 2 hours drive from their facility. New York City is about five hours from the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland, just outside of Washington DC. When I sent them the details of my case, though, the staff became intrigued, and asked me to join the study. In all, I made four trips to Bethesda, and went through every test the NIH Neuroimmunology team thought was appropriate. At first, they too labeled me "atypical PPMS", but in the end, they decided that I most likely do not have MS, as I certainly didn't fit any of the existing diagnostic criteria. They could not come up with a suitable alternate diagnosis, though, leaving me as something of a medical mystery (click here for a WK post I made about this at the time).

Interestingly, the NIH did raise the possibility that my disease could be ischemic in nature, meaning that it might have something to do with my circulatory system. So, I pursued CCSVI treatment, which did show an atypical blockage of my right internal jugular vein. I hate that word, atypical. Instead of the blockage being inside the vein, as is typical and usually caused by a valve problem, stenosis of the vein wall, or an anomalous membrane, my blockage appears to be caused by a muscle outside of the vein pinching it partially closed. Balloon angioplasty couldn't open this blockage, and the use of a stent would be quite dangerous, because the pressure put on it by the muscle pressing on my vein would lead to a high likelihood of stent fracture. I hope to undergo a second procedure some time in the next several months, to look for other blockages and see if there might be a way to address the atypical (ugh) blockage already found.

My primary neurologist says he still can't rule out a highly atypical case of PPMS, though he acknowledges my case is quite odd. Since MS is a diagnosis by exclusion, and we've been able to exclude practically every other possible cause for my condition, I suppose "atypical PPMS" it is. So, I still self identify as an MS patient.

Whatever you choose to call my disease, it's giving me a good ass whuppin'. My neuro and I (okay, maybe just I) have come to an understanding about the label, though: In my case, PPMS stands for the Peculiar Paralysis of Marc Stecker.

How atypical…