Yes, it’s that time of year again: the holidays are upon us. It’s incredible how they always manage to just kind of sneak up on you even though it’s impossible to miss the signs of the season, most notably the endless stream of holiday themed advertisements and TV commercials that these days start running even before Halloween.

Maybe it’s precisely because of that constant commercial bombardment with manufactured Christmas cheer that the actual day of the holiday inevitably comes as something of an anticlimactic shock. In an effort to simply maintain our sanity, perhaps we tune out all of the faux happy holiday chatter and go into a survival mode state of denial. After all, there are only so many Mercedes, BMW, Lexus, and Audi holiday advertisements one can watch before the brain simply perceives them all as white Christmas noise. And does anybody ever actually ever get a luxury automobile for Christmas? Anybody normal, I mean, folks in the “1%” not included? Back in 1981, my mother’s boyfriend gave me his recently deceased father’s 1970 Oldsmobile, but it wasn’t for Christmas and the car needed a new transmission and left rear quarter panel. Still, at 17, I was thrilled with my first set of wheels, and in my adolescent exuberance that 11-year-old Cutlass may as well have been Santa’s sleigh complete with flying reindeer.

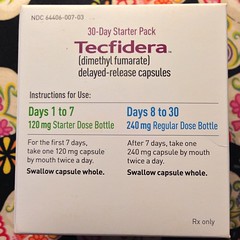

Whatever the reason, I always seem to find myself scrambling to order last-minute Christmas gifts for the folks on my list, even though these days my schedule isn’t exactly bursting at the seams. Thank heavens for the Internet, where even gimps can spread Christmas cheer without much fuss. With just a few clicks of the mouse, it’s ho ho holy crap, I just maxed out my credit card. But far be it from me to play the part of Scrooge, as I do derive great satisfaction in giving gifts to the ones I love. In fact, I honestly much prefer giving gifts to getting them. These days, given my limited physical capacities, there isn't really much that I need, except maybe a brand-new central nervous system, which I can only imagine would be especially hard to wrap and would make quite a mess under the tree…

In the spirit of giving I thought I’d provide a list some lesser-known MS nonprofits that would greatly benefit from the holiday largess of MS patients and those who care about them. In the world of MS nonprofits, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society is the great big hairy ape in the room. Due to its ubiquitous MS Walks, high public profile, and aggressive fundraising, the NMSS has become the face of MS to the general public. When most people think about making a donation on behalf of MS patients, it’s to the NMSS that the money flows. The National Multiple Sclerosis Society is to MS nonprofits as Kleenex is to tissues, melding in the public’s mind as one and the same.

In reality, though, there’s a plethora of worthy smaller MS nonprofit organizations out there, many of them starving for funds and some of them doing incredibly important work in the nuts and bolts research trenches that will with any luck eventually cure this damned disease. Trust me, when the cure comes it will most likely be from one of these little guys, not from the monoliths most often associated with MS research, who, though well intended, may be just a little too invested in the status quo, even if on an organizationally subconscious level. I by no means want to disparage the work being done by the NMSS, and the folks I know who work for the organization are all extremely caring and dedicated people, but there are lots of other guys in the sandbox who tend to get crowded out by the well hewn NMSS fundraising machine.

Here then are a handful of nonprofit MS research groups whose voices are all too often drowned out by the booming fundraising megaphones of larger organizations. The below groups all get the much coveted Wheelchair Kamikaze stamp of approval, and I’d urge WK readers to request that their family and friends who might be inclined to make MS related donations this holiday season to consider the following groups in lieu of some of the more obvious candidates.

♦ The Myelin Repair Foundation (click here) – As its name implies, the MRF is entirely devoted to researching strategies and methods for repairing the damage done by the MS disease process. Founded by Scott Johnson, himself a PPMS sufferer, the Myelin Repair Foundation aggressively seeks to break down the barriers that slow down medical research by encouraging collaboration rather than competition, and actively partnering with research groups and organizations pursuing the tangible goal of myelin repair and neuroregeneration.

Now maintaining its own research laboratories, the MRF has set its goal to have a therapeutic agent that repairs MS nervous system damage available to patients by 2019. That may seem like a distant date, but it’s only five years away, and for decades patients have been told that a cure for MS will be had within 10 years. So far that promise has been nothing but a lie, but I’m confident that the MRF stands an excellent chance of turning promises into reality. I’ve had the pleasure of having dinner with Scott Johnson, and I can personally attest to the drive and dedication of the man and his organization. The MRF is already making great strides towards reaching their goal, a goal that once achieved will have tremendous positive impact on each and every patient stricken with multiple sclerosis.

I’ve previously posted the below video, but it’s exceptionally well done and conveys the mission and vision of the MRF in an extremely personal and emotional fashion, while memorializing my late friend and comrade in arms, George Bokos, The Greek from Detroit. I’m featuring it once again in the hopes that readers will forward it to friends and loved ones, some of whom will hopefully choose to help the MRF achieve its audacious goal.

♦ The Tisch MS Research Center of New York (click here) – The privately funded Tisch Research Center is an integral part of the MS clinic at which I am treated. Headed by Dr. Saud Sadiq, the Tisch Center is at the cutting edge of MS research, investigating and innovating paradigm shifting methodologies for combating multiple sclerosis and repairing the damage that the disease inflicts on its victims.

In extremely exciting news, the Tisch Center recently received FDA approval to begin only the second US trial using adult stem cells to repair damaged central nervous system tissues in MS patients. Utilizing breakthroughs made through years of intense research at the Tisch Research laboratories, the clinical trial will use stem cells specifically targeted at repairing nervous system damage (neural progenitor cells) injected directly into the spines of trial subjects in an attempt to achieve the Holy Grail of MS treatment, the regeneration of cells damaged or destroyed by the MS disease process. One of the trial subjects will be noted journalist and author Richard Cohen, husband of TV personality Meredith Vieira, who, along with Dr. Sadiq recently appeared on The Dr. Oz Show to talk about this groundbreaking clinical trial. You can view clips from The Dr. Oz Show featuring the trio (click here-part one) and (click here-part two).

Dr. Sadiq is my MS neurologist, and I can testify to the man’s obsessive passion for finding the cure for MS and his deep compassion for the patients he treats. Dr. Sadiq is a bit of a maverick and a very “outside the box” thinker, a fiercely independent physician who refuses to permit pharmaceutical representatives to even enter his clinic so as to keep clear of the influence of Big Pharma. Given the frustrating and unrelenting nature of my illness, I consider myself lucky to have Dr. Sadiq on my side, as I’m confident that if anybody will come up with the answers I seek, it will be The Big Guy (as I affectionately call him). The Tisch MS Research Center of New York is certainly worthy of whatever tax-deductible donations come its way, as in addition to stem cell research the center vigorously conducts a wide range of studies specifically targeted at finding a cure for MS. Hopefully, the upcoming stem cell trial will culminate in results that will forever change the way MS is treated, and for the first time restore function pilfered by the disease.

♦ The Accelerated Cure Project (click here) – The ACP is an organization dedicated to speeding up the pace of multiple sclerosis research and treatment by engendering collaboration among researchers through a variety of mechanisms. Perhaps the most valuable resource provided by The Accelerated Cure Project is the ACP Repository (click here), a storehouse of blood and spinal fluid samples collected from over 3000 subjects, along with voluminous data on the medical and familial history of those subjects. These samples and data sets are available to scientists and organizations conducting research that can positively impact patients with MS.

The ACP Repository contains samples of Wheelchair Kamikaze blood and spinal fluid, which I understand is being kept in lead lined containers under the watchful eyes of Seal Team Six. Heaven forbid any WK derived substances fall into the hands of nefarious evildoers, as pure bedlam would be sure to follow. Labrador Retrievers would take their rightful place as the dominant species on the planet, and hordes of crazed wheelchair drivers would terrorize any who dared stand in the way.

All joking aside, The Accelerated Cure Project is devoted to the all-important goal of eradicating multiple sclerosis. Along with the ACP repository, The Accelerated Cure Project maintains The Multiple Sclerosis Discovery Forum (click here), an online community connecting, educating, and challenging MS researchers worldwide. Although intended for MS researchers, The Multiple Sclerosis Discovery Forum is a valuable resource for anybody interested in the latest MS info and research findings. Additionally, the ACP maintains the OPT-UP program (click here), a wide-ranging clinical study designed to evaluate the effectiveness of MS drugs in real-world settings, identify predictors an early indicators of response to specific drugs, and detect biomarkers specific to progressive MS.

The Accelerated Cure Project is an exceptionally important resource for MS researchers around the globe, and the organization has provided specimens and data for over 70 groundbreaking MS research studies. The biosamples, metadata, and interactive resources provided by the ACP are playing a vital role in research that could very well unlock the answers for which we as MS patients so ardently hope.

Well, there you have it, three smaller MS nonprofits all well deserving of charitable donations this holiday season (or any season, for that matter).

Please allow me to wish Wheelchair Kamikaze readers a very Merry Christmas, a happy belated Hanukkah, a tremendously good Kwanzaa, a happy Festivus (for the rest of us), or just a particularly good couple of weeks for those who don’t celebrate any of the aforementioned holidays. And of course, may all of us have a New Year filled with abundant health, happiness, and laughter.

As Charles Dickens wrote in A Christmas Carol, “It is a fair, even-handed, noble adjustment of things, that while there is infection in disease and sorrow, there is nothing in the world so irresistibly contagious as laughter and good humour.”

Amen to that…

![stella%20action%20cu[1] stella%20action%20cu[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgicV7jhfQgPleAcyTx2ZEpos_BLEE7VPKVZS4mNE-cQbJBMC7LcfDmJ0VK9sjPIzhI6zZly8H0vFJ-cLn1oxh8zoII3zPDaht78p_ccuioTLwiOBRd5V_LkWsk5VA5P9mkDmsGRSfLfLU/?imgmax=800)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=6f255460-31a4-4551-a20c-c9058d12bbbe)