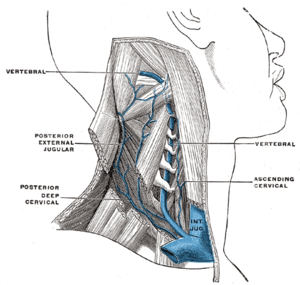

Image via Wikipedia

The subject of CCSVI (the vascular theory of MS) has proven to be incendiary, and has set the MS community ablaze. Initial studies into the hypothesis indicated substantial benefits could be gained by opening up the blocked veins in the neck and thorax of MS patients. These studies were soon backed up by an ever building wave of anecdotal patient reports of sometimes nearly miraculous improvements gained almost immediately after undergoing venoplasty, now known in the CCSVI universe as the Liberation Procedure.

In the wake of these reports, a tremendous amount of controversy has arisen, pitting MS societies and mainstream neurology against patients suddenly energized by hope, clamoring for access to a procedure they believe has a good chance to save them from the unrelenting ravages of the MS beast. Canada, which has one of the highest per capita MS rates in the world, has declined to even allow treatment studies of the liberation procedure to begin. Its single-payer health system refuses to recognize venoplasty as a potential treatment for MS, leaving Canadian MS patients with no options for treatment in their home country. The same situation holds true in most European countries. In the United States, the state of affairs is somewhat better, as an increasing number of physicians are offering the treatment to patients, although many health insurance companies won't cover it, and the cost of treatment is quite high. Additionally, waiting lists can extend for six months or more.

As a predictable result of this pent-up demand for treatment, a flourishing "medical tourism" industry has emerged around CCSVI, with clinics in Poland, Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Mexico, China, and India (and I'm sure I've forgotten a few) offering the procedure for a price, typically between $10,000-$20,000. It's been estimated that somewhere in the neighborhood of 2500 patients have visited these clinics, none of which have tracked the condition of their patients to any acceptable degree once the patients have departed for their home countries. Some of these patients have reported in at various sites on the Internet, but these patients probably represent less than 10% of the total patient population treated. Therefore, we have no good data on the effectiveness or safety of the treatments performed abroad.

The Liberation Procedure can take two forms: balloon angioplasty, in which tiny balloons are inserted into the veins and then expanded, thereby forcing open the veins, or stenting, a process involving the insertion of tiny mesh metal tubes into the veins, which when expanded prop the veins open. Often the two methods are used in conjunction, with patients receiving the balloon procedure in some veins, and stents in others. Both procedures carry the risk of clotting, although that risk is much amplified when stents are used. Because of this hazard, those who have undergone the Liberation Procedure are typically required to stay on a regimen of blood thinning anticoagulation medications for several weeks or months afterwards, necessitating the need for careful monitoring by qualified physicians to ensure the proper levels of medication are maintained. This aftercare can sometimes be hard to procure, as many physicians are reticent to treat patients for procedures that have been performed by foreign doctors and that they little understand. This problem has been especially prevalent in Canada, where the single payer health system has thus far refused to provide aftercare to patients that have gone overseas for "liberation".

In recent weeks, several troublesome (and in one case tragic) reports have begun to surface. Some patients returning from treatment in foreign clinics have experienced thrombosis (clotting) in their newly implanted stents, an extremely worrying condition that requires medical supervision (click here for article). In one truly horrifying episode, a young man who traveled to Costa Rica for treatment returned home to Canada, experienced thrombosis, and was turned away by local physicians when he sought their medical expertise. Ultimately, the patient returned to Costa Rica for treatment, and subsequently perished (click here for article). All of the patients in question had stents implanted in their jugular veins, which dramatically increases the chances of thrombosis when compared to balloon angioplasty, although that procedure too opens patients to potential problems with blood clots.

While the above incidents were transpiring, a conference on CCSVI was held at the annual ECTRIMS (European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis) in Gothenburg, Sweden. Many CCSVI research studies were presented, which are discussed in detail in the recently released article on Medscape.com (click here for article-you may be required to register at the site for access, a process which only takes a few minutes and is well worth the effort. Medscape is terrific resource for medical information). This article is quite long and offers an in-depth look at some very important research. It should be required reading for all patients interested in CCSVI.

The data presented at ECTRIMS was often in conflict, with some studies contradicting others, but the general consensus seems to be that while there is an identifiable correlation between CCSVI and MS, there is question as to whether CCSVI is the cause of MS. Rather, it may be a condition that is a result of the same disease process that causes the CNS damage seen in Multiple Sclerosis, or very possibly could contribute to the severity of the disease. It's quite possible that all of these scenarios may hold true, as MS differs so much from patient to patient that a variety of factors may result in its causation. In some patients CCSVI may play a major role in their MS, but in others it may play no role at all.

Given the above developments and wealth of new information, I feel compelled to offer the following words of caution. I know this message will not sit well with the most fervent CCSVI advocates, but I feel I would be remiss in not offering them.

While I am still a strong believer that CCSVI will prove to play a major role in unraveling the MS puzzle, I think that it is vital that patients use extreme discretion when choosing whether or not to undergo the Liberation Procedure, particularly if they must fly to far off destinations to procure treatment. According to one of the most experienced physicians performing the liberation procedure, Dr. Gary Siskin in Albany, New York, only about one third of patients treated receive dramatic improvements in their condition. Another third experienced minor benefit, and yet another third received no benefit at all. Furthermore, the rate of restenosis (veins closing back up) after balloon angioplasty is quite high, somewhere in the neighborhood of 50% within 12 months of treatment. These statistics alone should give patients some pause, as 66% of treated patients do not get the level of benefit they hoped for, and of those that do, 50% revert back to their previous condition, necessitating the need for additional procedures. This translates into 17% of patients who get liberated with the balloon method finding the lasting relief they sought.

The use of stents should be seriously questioned. In addition to the news reports above, Internet forums are revealing yet more patients suffering from stent thrombosis, and through this blog I've received numerous e-mails from other patients struggling with this problem. Stent thrombosis is only one of the potential hazards associated with the devices. The long-term failure rates of stents placed in the jugular veins is completely unknown. Most of the stents now being used were originally designed for use in thoracic arteries, where they are not subject to the nearly constant bending, twisting, and torque that they undergo when implanted in the extremely flexible human neck.

Data collected from two other patient populations that commonly receive venous stents (patients suffering from some cancers, and end-stage renal disease patients undergoing dialysis) is not especially encouraging. The failure rate of stents placed in dialysis patients has been found to be close to 50% after one year (click here for study). Although direct comparisons between disparate patient populations cannot be made, this data does provide reason for concern. Thus far, CCSVI patients treated with stents have not reported any instances of stent failure. However, the longest any of these patients have had stents implanted is only about 18 months, and the vast majority of patients fitted with stents have only received them in the last several months. I fervently hope that we do not start seeing a rash of stent failures in the months and years to come. The possibility can't be discounted, though, and only time will tell.

In conclusion, although CCSVI does hold tremendous hope for the future management of multiple sclerosis, we are presently in only the early infancy of investigation into the hypothesis and its relevance to the MS disease process, and of the practice of treating the condition with venoplasy. Beyond a doubt, future Liberation Procedures will bear little resemblance to those being done today, as new devices specifically designed for the task come on market, and the techniques and practices used to implement them are refined.

My heartfelt advice is that all those except the most desperate (and by that I mean patients with extremely aggressive disease who are quickly hurtling towards total disability) simply wait for 6 to 12 months before embarking on a quest for liberation. This will at least give some time for research to begin to catch up to patient expectations, and for physicians to better understand the best methods used to address the venous anomalies being found in MS patients.

I echo the warnings of virtually all of the most prominent physicians in the field, Dr. Zamboni included, that no patient resort to medical tourism in their quest for liberation. The risks of doing so are very real, particularly when the use of stents is involved. Balloon angioplasty is a much safer option, but the high incidence of restenosis means that many patients spending tens of thousands of dollars on treatment in foreign lands will find whatever gains they experienced lost, and will suffer not only from a return of their symptoms, but from broken hearts and broken bank accounts.

I fully understand the almost irresistible pull to get the disease taken care of NOW. I am close to being one of the desperate, if I'm not already there. This is why I chose to undergo a procedure this past March, which revealed a significant venous blockage but was unable to get it opened (mine is a very atypical case; the blockage is caused by a muscle outside of the vein pinching it almost closed). Hope is a powerful intoxicant, one that has been long absent for the vast majority of MSers. But we cannot and must not allow hope to eclipse reason. We all would like to see CCSVI advance as quickly as possible, but unfortunate events such as those recently reported will only provide fodder for those who would see the hypothesis relegated to the dustbin. Stay strong, friends, and act with extreme diligence.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=01cfbacb-cf87-4b81-a144-3f936e66d3d3)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=9441d7be-1d2b-4550-940b-8ed227d04a71)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=6e419ad3-6a61-4b45-968b-32ed32a1055b)